QUICK SUMMARY

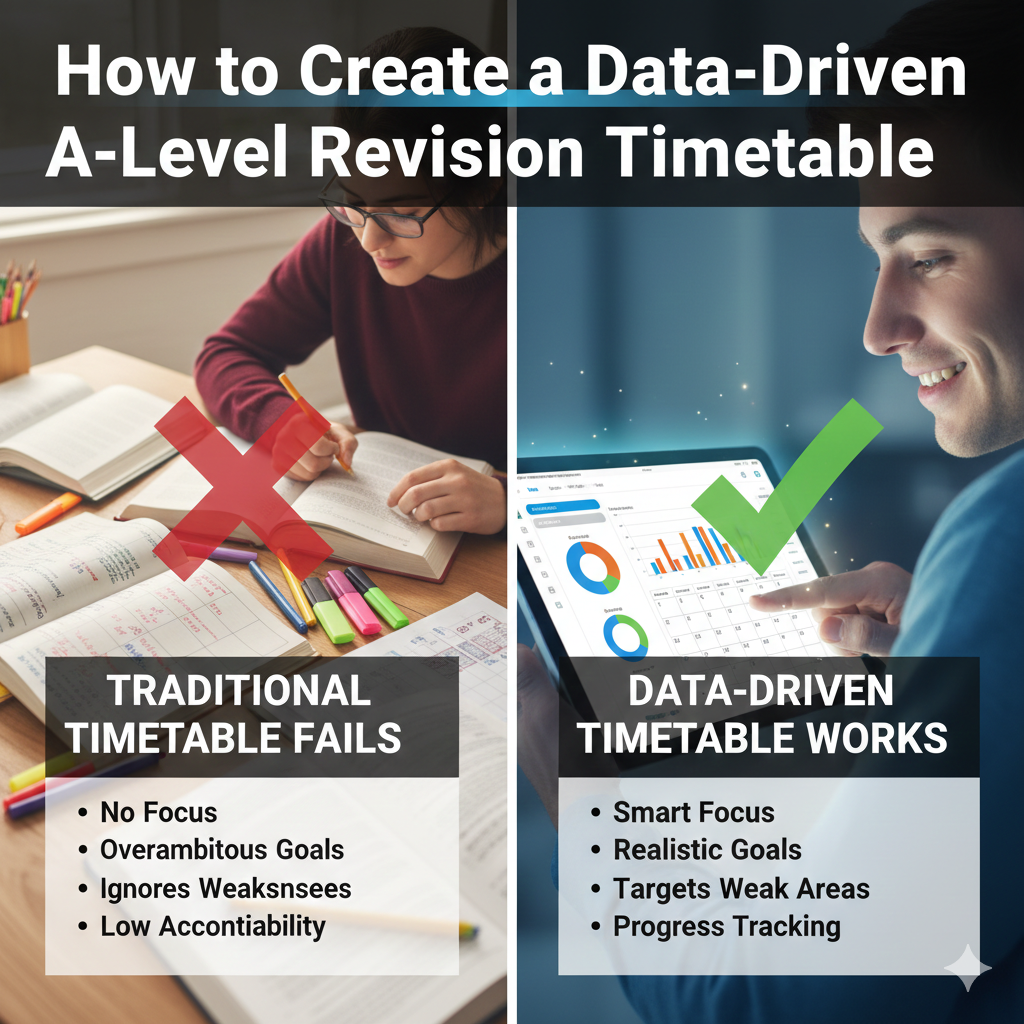

Most students searching for an A-Level or IGCSE revision timetable end up creating colour-coded schedules that look organised but fail to improve grades.

The problem isn’t effort. It’s a strategy.

A revision timetable prioritises high-weight topics, past paper frequency, and examiner expectations. Not just available study time. This guide explains how to create a data-driven A-Level revision timetable using a 5-step exam-optimiser system.

WHO THIS GUIDE IS FOR

This guide is for:

- Students preparing for mocks, resits, or final board exams

- Students following Cambridge (CAIE), Edexcel, or AQA specifications

- Students aiming for A or A* grades

Not for:

- Students looking for last-minute cramming tricks

- Students who want motivational study tips without structure

- Students are unwilling to use past papers or examiner reports

TABLE OF CONTENT

- What Is a Data-Driven A-Level Revision Timetable?

- Why Traditional Revision Timetables Fail

- The Exam-Optimiser 5-Step Revision Framework

- What Makes This Different from Generic Timetable Guides?

- Final Summary

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Is a Data-Driven A-Level Revision Timetable?

A data-driven A-Level revision timetable is a strategic study plan that prioritizes topics based on objective evidence rather than intuition. It uses exam specification mapping, past paper frequency, and personal performance data to allocate time toward high-yield, weak areas. This ensures study hours are focused on the topics most likely to appear and improve your final grade.

Why Traditional Revision Timetables Fail

The standard revision timetable is a decorative lie. We spend hours choosing the perfect hex codes for “Organic Chemistry” and “Macroeconomics,” only for the entire system to collapse by Wednesday afternoon.

If you’re revising passively, read our breakdown of why most revision systems fail and what actually works instead.

The Planning Fallacy

The “Planning Fallacy” is a psychological bias where we underestimate the time required for a task, even when we know similar tasks have taken longer in the past. In the context of A-Levels and IGCSEs, this creates a compounding disaster.

Optimism Bias: You schedule “Cell Biology” for 1 hour because it sounds reasonable.

Reality Check: You encounter a difficult concept (like Oxidative Phosphorylation), get stuck for 2 hours, and fall behind.

Domino Effect: Because your schedule is a rigid block of time, one delay knocks the entire week out of alignment. You end up skipping the “hard” topics later in the week just to stay “on schedule.”

The Result: You feel like a failure for not sticking to the plan, leading to “Revision Guilt” and total abandonment of the timetable.

Time-Based vs. Data-Based Planning

Traditional timetables fail because they are time-based, not data-based. Students often over-prioritise comfortable subjects and under-prioritise high-impact topics. Data-Based Planning ignores the clock and focuses on the Target.

| Feature | Time-Based (The Failure) | Data-Based (The Success) |

| Primary Metric | Hours spent at the desk. | Specific marks gained in practice. |

| Flexibility | Rigid; one delay breaks the day. | Fluid; shifts based on topic difficulty. |

| Topic Choice | “Whatever I feel like” or “What’s next.” | Highest frequency + lowest confidence. |

| Mindset | “I worked for 4 hours, I’m done.” | “I mastered 3 bullet points, I’m done.” |

The Exam-Optimiser 5-Step Revision Framework

The Exam-Optimiser system replaces guesswork with a repeatable, five-step loop. The Exam-Optimiser Revision System solves this by combining:

- Syllabus mapping

- Past paper frequency analysis

- Weakness diagnosis

- Strategic time allocation

- Iterative testing & adjustment

This ensures your revision focuses on what actually affects marks, not just what feels important.

Step 1 – Specification Mapping

The biggest mistake students make is revising from a textbook. Textbooks are written to teach a subject. Exam Specifications are written to grade you. Mapping is the process of stripping away the “fluff” and focusing only on what earns marks.

When mapping your specification, highlight command verbs. They signal the level of response required and directly influence how you should revise and practise answers.

What to Do:

A student must first obtain the current version of the syllabus from the relevant awarding body (e.g., Pearson, Oxford, or Cambridge). This document should be treated as a checklist. The student should list every sub-topic and break them down into discrete “learning objectives.”

By breaking the syllabus into units, the student transforms a massive volume of information into a series of achievable milestones. This granular approach enables the creation of a “Topic Tracker” that ensuresno part of the curriculum is overlooked.

Why It Works:

Specification mapping is effective because it forces the student to adopt the examiner’s perspective. Educational psychology suggests that “metacognition” (the ability to think about one’s own thinking) is a primary indicator of academic success. This method ensures that the student is studying at the correct “depth.”

For example, if a Biology specification requires a student to “describe” a process rather than “explain” it, the student can save time by not over-learning unnecessary mechanical details.

Case Study:

I once worked with an A-Level Physics student who spent three days memorizing the history of Michael Faraday and the conceptual “beauty” of fields for his Electromagnetism unit.

The Problem: He was studying for a history test, not a Physics exam.

The Mapping Fix: We pulled the spec. It revealed that 80% of the marks for that unit were tied to calculating Magnetic Flux Density (B = Phi / A) and applying Fleming’s Left-Hand Rule.

By mapping the spec, he realized his “deep understanding” was irrelevant for the marks available. We pivoted his revision to calculation drills and hand-rule diagrams, moving his practice scores from a C to an A in a week.

Step 2 – Past Paper Frequency Analysis

If Step 1 was about knowing what can be asked, Step 2 is about knowing what will likely be asked. Exam boards are creatures of habit. They have a finite pool of marks to award and specific “heavyweight” topics they must test every year to maintain standards.

What to Do:

Stop doing past papers as “practice” for a moment and start using them as data sources.

- Secure the last 5–10 years of past papers and their mark schemes.

- Create a spreadsheet or a simple table. Every time a topic from your Step 1 map appears, record the total marks assigned to it.

- Look for patterns. You’ll quickly notice that while “Topic A” appears every year for 10 marks, “Topic B” only appears as a 2-mark multiple-choice question every three years.

Why It Works:

In education, the Pareto Principle holds: roughly 80% of the total marks in an exam usually come from 20% of the specification. You stop treating a 1-mark definition with the same respect as a 12-mark essay question.

Once you see that “Calculations of Rf values” has appeared in 9 out of the last 10 Chemistry papers, it becomes a “must-win” topic rather than an optional one. It gives you “permission” to spend less time on low-frequency, low-mark topics that often confuse students and drain their energy.

Outcome:

By the end of this step, your revision list is no longer in alphabetical order. It is ranked by Mark Density.

| Priority | Topic Type | Action |

| High | Appears 80%+ of the time | Master every variation of this question. |

| Medium | Appears 40-50% of the time | Ensure basic conceptual understanding. |

| Low | Appears <10% of the time | Review once; don’t lose sleep over it. |

Step 3 – Weakness Diagnosis

Most students spend 80% of their time revising topics they already understand because it feels productive. This is the Fluency Illusion. True progress only happens when you stop “reviewing” and start “diagnosing.”

Formula for Weakness Scoring: Weakness Score = Number of Incorrect Questions/ Total Attempted × 100

What to Do:

To find your gaps, you need to fail in a controlled environment.

- Take a past paper section under timed conditions without your notes.

- Use the official mark scheme. If your answer isn’t exactly what they want, give yourself zero.

- Don’t just look at the total score. For every mark lost, assign a category:

- Knowledge Gap (K): “I’ve never seen this before.”

- Application Error (A): “I knew the fact, but didn’t know how to use it in this scenario.”

- Exam Technique (T): “I missed the keyword ‘Describe’ and ‘Explained’ instead.”

Why It Works:

Data-driven diagnosis forces you to look at the “Red” topics you’ve been avoiding. You can’t argue with a 2/10 score on a stoichiometry drill. It removes the “I think I’m okay at this” bias.

Instead of re-reading a 300-page textbook, you are now only looking for the specific information required to fix a “Knowledge Gap.” By marking your own work, you see exactly how the examiner thinks, which builds “Exam IQ” alongside content knowledge.

Outcome:

The final study schedule should not be an even distribution of all topics. Instead, it should be weighted toward the “Content Gaps” and “Application Errors” identified during the diagnosis phase. This ensures that every hour of study provides the maximum possible increase in the final grade.

Step 4 – Strategic Time Allocation

Now that you have your data, it’s time to build the schedule. Forget “Monday is History day.” In a data-driven system, your time is a currency you invest where the Return on Investment (ROI) is highest.

What to Do:

Use the data from Steps 2 and 3 to plot your topics. Your goal is to find the “Sweet Spot”. The intersection of High Exam Frequency and Low Current Confidence.

- Zone 1: High frequency, Low confidence. 70% of your time goes here.

- Zone 2: High frequency, High confidence. 20% of your time goes here (active recall only).

- Zone 3: Low frequency, Low confidence. 10% of your time. Don’t let these “difficult” but rare topics derail your schedule.

Why It Works:

If you are already at 90% mastery in a topic, spending another five hours on it might only net you 1 or 2 extra marks. That is an inefficient use of your life.

- By moving a “Red” high-frequency topic to “Amber,” you could potentially gain 10–15 marks in the same five-hour window.

- You tackle the hardest, most rewarding tasks when your brain is freshest, rather than “saving them for later” (which usually means never).

- It prevents “Revision Fatigue” because you see rapid improvement in your practice scores.

Outcome:

Your timetable now looks like a tactical strike plan. This approach ensures that every minute you spend at your desk is directly linked to a potential mark on the final paper.

Step 5 – Iterative Testing & Adjustment

Data is only useful if it’s current. A common mistake is sticking to a “Week 1” plan in “Week 6.” Your revision must evolve as your knowledge grows, moving from content absorption to exam mastery.

What to Do:

Treat every week like a mini-sprint. At the end of every seven days, you must re-validate your assumptions. Complete one full-length exam section for your “Red” topics. If you scored >80% on a “Red” topic, move it to “Amber.” If an “Amber” topic hit >90%, it’s now “Green.” Look at your Priority Matrix from Step 4. Drag the remaining “Red” topics to the top of next week’s schedule.

Case Study:

I worked with an English Literature student who had mastered her “Knowledge Gaps” (she knew every quote by heart). However, her weekly tests showed her marks were still plateauing at a Grade 6.

The Diagnosis: By reviewing her test data in Step 5, we realized she wasn’t losing marks on content, but on Structure and Analysis (AO2).

The Adjustment: We stopped all quote memorization. For the next two weeks, her “Iterative Plan” focused 100% on timed essay introductions and “PEEL” paragraph drills.

The Result: By adjusting her plan based on weekly evidence, she jumped to a Grade 9 in her final mocks.

Outcome:

By the time you reach the final week before your exams, your “Red” list should be empty. You aren’t “revising” anymore; you are simply maintaining peak performance.

What Makes This Different from Generic Timetable Guides?

Most revision advice focuses on the “vibes” of studying. Using pastel highlighters, Pomodoro timers, and “aesthetic” desk setups. While those might make you feel productive, they don’t actually correlate with higher grades.

The Exam-Optimiser System is built on the same principles used by hedge fund analysts and software engineers: Input vs. Output Efficiency. We don’t care about how many hours you sit at your desk; we care about the “Mark-Yield” of those hours.

Implementation Timeline: The 10-Week Countdown

A data-driven plan isn’t built in a day. It requires a shifting focus, moving from heavy data gathering to high-intensity output. This 10-week framework ensures you don’t peak too early or leave the “hard stuff” until it’s too late.

Phase 1: The Audit (Weeks 1–2)

Goal: Build your map and identify the “Gold Mines.”

Week 1: Download specifications for all subjects. Complete your Specification Mapping (Step 1).

Week 2: Run a Frequency Audit (Step 2) on the last 5 years of papers. Mark your “High-Frequency” topics.

Phase 2: The “Red Zone” Sprint (Weeks 3–6)

Goal: Aggressive growth by tackling the most rewarding weaknesses.

Week 3-4: Focus 80% of your time on High-Frequency / Red topics. Use “Blurting” or the Feynman technique for content.

Week 5-6: Transition to Amber topics. Start doing “open-book” past paper questions to bridge the gap between knowing and applying.

Phase 3: The Iteration Loop (Weeks 7–9)

Goal: Polish exam technique and fix “Silly Mistakes.”

Week 7: Full-length timed mocks. Perform a Weakness Diagnosis (Step 3) on the results.

Week 8-9: The 70/20/10 Allocation (Step 4). Tighten up your “Exam Technique” (AO2/AO3 marks). Move topics to “Green.”

Phase 4: Peak Performance (Week 10)

Goal: Maintenance and mental readiness.

Final Week: No new content. Quick-fire active recall for “Green” topics. Review your “Error Taxonomy” to remind yourself of previous pitfalls.

Final Summary

The Exam-Optimiser Revision System isn’t theoretical, it’s the structured approach. We use when guiding A-Level and IGCSE students through exam preparation. Instead of guessing how many hours to study, we analyse specifications, track the frequency of past papers, diagnose weaknesses, and adjust study plans weekly based on measurable progress.

If you’re preparing for exams, open your specification today and start ranking your topics by mark weight. That single action changes everything.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which Tools or Resources Help?

Use specification-matched question banks and official past papers from your awarding body. Past papers from exam boards (AQA, Edexcel, OCR) and apps for spaced repetition like Quizlet are essential for input data.

How Do You Track Progress?

Maintain an error log noting mistakes, correct methods, and retest scores. Visualize with charts of topic completion and average marks. Use mock exams for full simulations, comparing scores over time to measure improvement (aim for 20-50% gains via retrieval practice).

How Many Hours Should an A-Level Student Revise Per Week?

Instead of fixed hours, use this formula: Study Hours = Topic Weight × Weakness Score × Available Time

How Many Past Papers Should You Analyse?

Analyse 5–10 years of past papers. Five years reveal reliable frequency trends. Ten years gives stronger statistical confidence.

Key Takeaways

- Revision should be mark-weighted, not time-weighted.

- 80% of marks often come from 20% of topics.

- Diagnose weaknesses before allocating time.

- Re-test weekly and reallocate effort.

- Stop tracking hours. Start tracking marks.